When The Children Die

By Tristin Allaire

June 06, 2021

Introduction to Children in foster care, and the News we Don’t Notice.

Royalty-Free Music from Bensound “Once Again”, by Benjamin Tissot

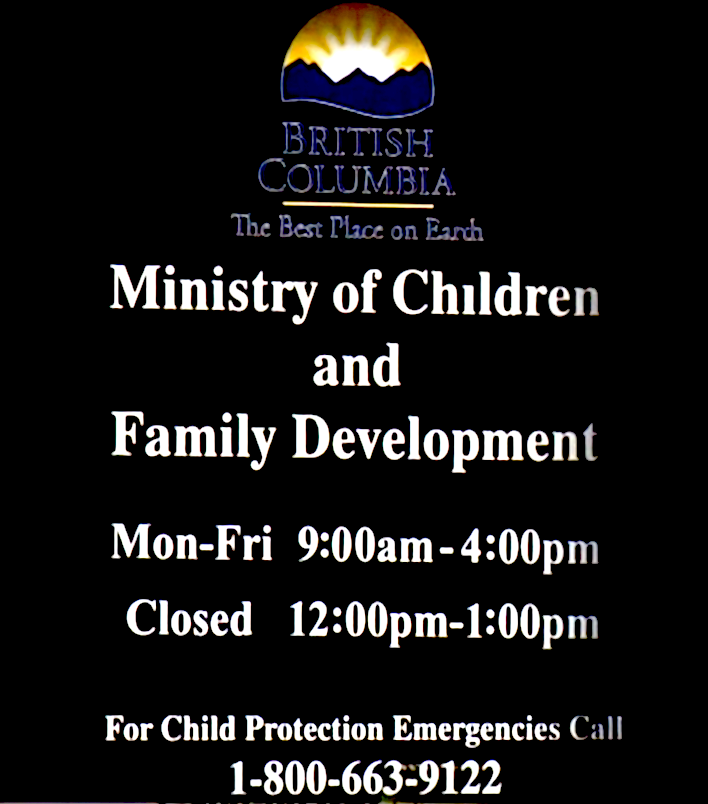

The Ministry for Taking Children from Families, Tristin Allaire, July 9, 2021

When Alexander and his older twin brothers, Devon and Everett, heard they were being adopted, they did not know what to think. Having spent their entire lives in the care of the Ministry of Children and Family Development, the boys did not know any other way of living. They were excited and anxious about being removed from Vancouver Island to live in a distant and unknown place: The Mainland. The boys received the news in early August 2000, shortly after the death of an unnamed indigenous child led to the discovery of multiple foster children living in appalling conditions.

The start of the mass rehoming of foster children located in the greater Nanaimo area began after the death of an unnamed indigenous child in the nearby city of Duncan. The deaths of 885 children have been linked to the Ministry between 2008 and 2016, not including injures resulting from attempted suicide, assaults, trauma, and accidents, of which there were over three thousand in the same period (Sherlock, T. 2017).

The number of publicly reported foster-care deaths on the Government of Canada statistics website is relatively low, and knowledge of the disparity is limited. However, according to Ricksen Stewart (2017), “[i]n Alberta, within the span of 14 years between 1999 and 2013, 741 children died while in care or while receiving child welfare services.”

So when an internal reform of the Island Ministry was called for, and multiple children in care were rehomed, where was the news van? Where are the historical articles about the event? Who, if anyone, was charged? Reviewing other high profile deaths of children in the Ministry’s care, one only has to look at Paige Parsons’ 2020 CBC article about a four-year-old indigenous girl named Serenity (last name protected by publication bans), who was starved, mistreated, and eventually died in 2014, of blunt force trauma to the head while in care. Two years after her death, no charges had been laid, and six other children, including Serenity’s siblings, still lived in the home (Parsons, P. 2020).

Another example is the deaths of the First Nations children in the care of Xyolhemeylh, a small social services society located in British Columbia’s Fraser Valley region: Traevon Chalifoux-Desjarlais was stabbed to death at age 17, Alex Gervais committed suicide at age 19, Santanna Scott-Huntinghawk aged out at 19 and died of a fentanyl overdose alone in a tent, and two-year-old Chassidy Whitford was murdered by her father while in Xyolhemeylh’s care. Even in light of media coverage and public outcry, very few things have changed within the Ministry (Angela Sterritt 2020).

Super 8 Motel, houses the neglect of MCFD, and the death of Alex Gervais. Abbotsford, BC. Tristin Allaire, May 24, 2021

In the light of Mass graves, The shoes of indigenous children, Left on the gate. O.M.I Cemetery, Mission City Heritage Park. BC. Tristin Allaire, July 16, 2021

Unfortunately, almost no reports of deaths in the foster system exist when Alex and his brothers were in care because of the Ministry’s efforts to suppress media coverage and minimize the damage to the agency’s reputation. Many of the children were First Nations, seized from struggling homes on reserves, away from parents who had survived the tragedy in residential schools. In addition, social workers often treated indigenous families as more at-risk than other ethnicities. As a result, indigenous children were more quickly removed from their homes than other ethnicities for the same transgressions.

The remnants of a crumbled residential school, and the culture stolen in its wake. Residential School outbuilding, Mission City Heritage Park, BC. Tristin Allaire, July 16, 2021

Alexander and his brothers were three of the few Caucasian children grouped into this massive rehoming project, though for a completely different reason. After their parents lost custody and parental visitation rights, the adults began taking classes and building a healthier environment for their families. Both parents made multiple pleas to the court system to return their children and were coming close to a favourable legal outcome. They had performed their due diligence, had stable jobs, and we’re on track to have their children released to them. However, the Ministry still did not believe the boys’ parents were fit to take on the responsibility. The foster parents and the boys’ direct social care worker devised a permanent solution: reaching out to the boys’ extended family and requesting that someone take them in through the process of adoption. A great-aunt and great-uncle received the Ministry’s request and agreed to the proposal.

As the parents got closer to regaining custody of their children, the Ministry pushed the adoption process, neglecting vital home checks, classes, and the due process of adoption procedures. In just over six months, the three boys were packed onto a ferry with their new guardians. The adoption process, on average in British Columbia, should take two to three years. Now they were headed off the Island to live hundreds of kilometres away from everything they knew. The boys’ biological parents were only informed after the process was completed, and they had no way to appeal the decision or regain custody of their children.

Should we wonder if this situation is unique? Are examples of the government breaking protocols and hiding child deaths rare or commonplace, and should Canadians stand together and demand change? We can ask what happened to these three boys after their rushed adoption, or we can imagine that they lived a fairy-tale ending, but what about the other brothers, sisters, and single children we do not know about? Do we need a sad article for every one of them before people realize that their suffering, just out of view, still exists? Even if children in care do not affect your family directly, it affects this nation, and its morality, as a whole, and so much more could be done to support children who are currently given no chance at a real life.

It’s time Canadians stand up for the rights of our most precious resource and consider calling your local M.P. to demand budgetary reforms and increased training levels for those involved in the care of foster children. If you have the ability to take on a caregiver role, please consider the life-changing gift of adoption. There is some poor child out there literally dying to have a home.

References

“Increased Risk Groups | Youth.Gov.” Youth.Gov, 2020, youth.gov/youth-topics/youth-suicide-prevention/increased-risk-groups.

Parsons, Paige. “In Depth: Serenity — A Life Cut Short.” Www.Cbc.Ca, 2020, newsinteractives.cbc.ca/longform/serenity-longform-investigation-feature.

Sherlock, Tracy. “Number of B.C. Kids-in-Care Deaths, Critical Injuries Jump Dramatically.” Vancouversun, 10 Feb. 2017, vancouversun.com/news/local-news/number-of-b-c-kids-in-care-deaths-critical-injuries-jump-dramatically.

“Statistics – Children Involved with the Ministry of Children & Family Development – Province of British Columbia.” Government of Canada, 1 Apr. 2021, www2.gov.bc.ca/gov/content/family-social-supports/data-monitoring-quality-assurance/reporting-monitoring/statistics.

Sterritt, Angela. “Other Deaths Linked to B.C. Aboriginal Agency Running Group Home Where Indigenous Teen Died.” Www.Cbc.Ca, 10 Nov. 2020, www.cbc.ca/news/canada/british-columbia/agency-runs-group-home-indigenous-teen-died-in-bleak-track-record-1.5774854.

Stewart, Riksen. “Deaths of Children in Government Care Skyrocket in Canada.” World Socialist Web Site, 6 Sept. 2017, www.wsws.org/en/articles/2017/09/06/cafc-s06.html.

Research Table: Who, What, Where, When, Why and How of My Story

|

Element |

Research |

Source (APA style) |

|

Who? |

Myself and older brothers, along with an uncounted number of foster children. |

N/A |

|

What? |

They were forced into an expedited adoption to suit the Ministry’s for Family and Children’s needs, along with the death, maltreatment, and abandonment of many others over decades. Research on the death rates of children in or related to government care. Research high profile cases of other Canadian foster-related deaths. |

“Increased Risk Groups | Youth.Gov.” Youth.Gov, 2020, youth.gov/youth-topics/youth-suicide-prevention/increased-risk-groups. Parsons, Paige. “In Depth: Serenity — A Life Cut Short.” Www.Cbc.Ca, 2020, newsinteractives.cbc.ca/longform/serenity-longform-investigation-feature. Sherlock, Tracy. “Number of B.C. Kids-in-Care Deaths, Critical Injuries Jump Dramatically.” Vancouversun, 10 Feb. 2017, vancouversun.com/news/local-news/number-of-b-c-kids-in-care-deaths-critical-injuries-jump-dramatically. “Statistics – Children Involved with the Ministry of Children & Family Development – Province of British Columbia.” Government of Canada, 1 Apr. 2021, www2.gov.bc.ca/gov/content/family-social-supports/data-monitoring-quality-assurance/reporting-monitoring/statistics. Sterritt, Angela. “Other Deaths Linked to B.C. Aboriginal Agency Running Group Home Where Indigenous Teen Died.” Www.Cbc.Ca, 10 Nov. 2020, www.cbc.ca/news/canada/british-columbia/agency-runs-group-home-indigenous-teen-died-in-bleak-track-record-1.5774854. |

|

Where? |

Nanaimo, BC and the entire nation of Canada |

Stewart, Riksen. “Deaths of Children in Government Care Skyrocket in Canada.” World Socialist Web Site, 6 Sept. 2017, www.wsws.org/en/articles/2017/09/06/cafc-s06.html. |

|

When? |

The early 2000s to current times, and decades before. |

No attribution |

|

Why? |

In an attempt to save the agency’s reputation and show social workers were performing the duties required of them, a wave of random home checks was done on children throughout the Vancouver Island foster region. Hundreds of children were found to be in poor living conditions at the best of times. To stop media coverage of the events, the Ministry hid behind privacy laws and media publication bans. Biological parents without visitation rights were not informed. As a backup plan, the Ministry also moved many children, some of whom merely swapped from one home to another. On paper, the children had been rescued, yet, in reality, they had only been shuffled like a deck of cards, stuck in the same old box. My brothers and I were grouped into this operation to expedite the process of adoption, so our biological parents could never regain custody. |

|

|

How? |

The Ministry has lost federal funding and misuses what little they have. Their staff are undertrained and underqualified. In addition, the Ministry is known to withhold or misuse resources to save money, leading to poorly qualified caregivers, low-quality institutions, and minimal resources for foster children. |

Stewart, Riksen. “Deaths of Children in Government Care Skyrocket in Canada.” World Socialist Web Site, 6 Sept. 2017, www.wsws.org/en/articles/2017/09/06/cafc-s06.html. |